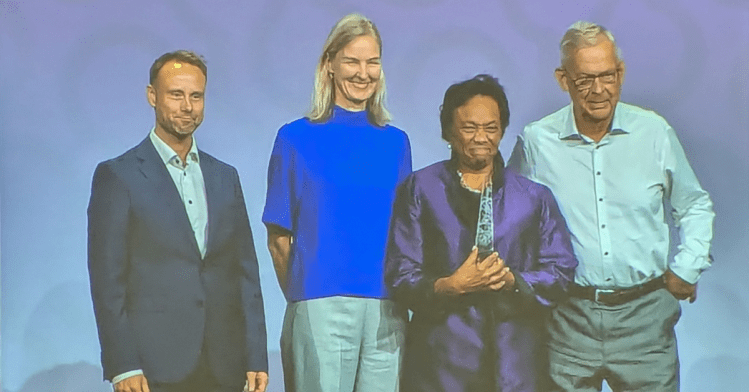

The Alzheimer’s Association® presented six scientific awards at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference® 2024 (AAIC®), recognizing researchers for their varied expertise, noteworthy achievements and innovative contributions to the field of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia science. One of these awards was bestowed to North Carolina researcher Goldie S. Byrd, Ph.D. for her significant contributions to Alzheimer’s and dementia research.

Dr. Byrd is the recipient of the Bengt Winblad Lifetime Achievement Award, named after one of the co-founders of AAIC. Byrd is a professor of social sciences and health policy and director of the Maya Angelou Center for Health Equity at Wake Forest University School of Medicine. She conducts research on the genetics of Alzheimer’s disease in persons of African descent. A primary focus for her is the inclusion of special populations, particularly African Americans, in Alzheimer’s research and clinical trials. At North Carolina A&T State University, Byrd founded the Center for Outreach in Alzheimer’s Aging and Community Health to increase awareness of Alzheimer’s disease in minoritized communities and to connect these communities to research. She has won numerous awards for her community-engaged research that addresses equity and inclusion in Alzheimer’s research. This includes a recent honor as a Most Influential Person of African Descent, for equity research, sponsored by the United Nations.

Taylor Wilson, an Alzheimer’s Association staff research champion for NC, SC & GA had a chance to speak with Dr. Byrd following her honor. Their conversation is below.

How many years have you been attending AAIC?

I have attended this conference since 2009. It was held in Vienna, Austria, where the (Alzheimer’s) Association asked me to do a press conference because we had just begun to focus on recruiting African Americans into genome-wide-associated studies. The now AAIC was called the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference on Alzheimer’s Disease (ICAD). At that time, there were so few African Americans in any studies in Alzheimer’s disease, while many investigators had interest. We showed that engaging this population was an important first step toward its engagement. In spite of investigators’ doubts, we showed that it could be done, with authentic relationships and increased awareness .

I was actually on sabbatical at Duke University when we began this work, and there was hardly anything in the literature in genomics and African Americans. My recommendation to understand genetic architecture of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in this population, was met with some concern because investigators had not been successful in ascertaining enough in this disease among African Americans, for many reasons. In fact, the group we began working with is the same group we are working with now and have been working with, since 2002. Almost all of the genomic studies had been done in whites before we started working with our group.

The Association asked me to talk about what we did (to be successful). We shared that we went to the African American community, conducted feasibility studies, asked people about their research experiences, perceptions, barriers and concerns. We also asked if they had ever been asked (to participate). We asked over 500 African Americans what they needed, regarding AD, and what they needed from us, to even begin to talk about research, to talk about genomics projects. We had to go to NIH to get funds for the community engagement to get it off the ground first.

From that study, we learned that we needed to create some trusting relationships with the community. We began a huge outreach and engagement campaign in North Carolina. We began hosting large events and conferences where we brought people together to learn from us and from each other. The community wanted a support group, so we created one, one of the first African American support groups in the state. From there we worked the several community groups including the North Carolina Alzheimer’s Association to create innovative learning opportunities. We hosted lunch and learns for affected families and an annual caregiver conference. North Carolina A&T State University gave us space to create the Center for Outreach in Aging and community Health (COAACH).

The institution at the time gave us a (community) center where we could bring people in for support groups and for “Lunch and Learns”. We just had a place for people to gather to learn and to be connected with our team. And so we just started giving, we started giving before we asked the community for anything.

What role do you feel minority researchers play in the Alzheimer’s disease research space in terms of working with minority populations?

Researchers from minoritized groups play a huge role in working with minoritized populations. They are trusted voices and the literature shows that when there is some concordance between research participant and researcher, there can be greater trust and greater involvement. While this is not always a necessity, research participants appreciate having researchers and study staff who look like them, and who have common cultures and experiences. This is particularly true when the research involves invasive protocols such as blood draws, scans, lumbar punctures or brain donations. It is really exciting to see how the field is growing and becoming more diverse.

One might ask the question, “Is that racism or prejudice?” No, it is a connectivity and people tend to relate culturally when there is someone on the team who can speak to that community’s values, family constructs, or historical perspectives. There are many sensitivities around traumas in research, science, and medicine, so there is no wonder that diverse groups would be concerned about connectivity and cultural appropriateness.

People ask us “why did we focus on African Americans”, and it isn’t because we are being exclusive, it is because we are trying to be inclusive and close some very wide gaps.

What are some of the biggest shifts in research trends you’ve seen in your time participating in AAIC?

I think commitment to inclusion in research is exciting. We still have such a distance to go to achieve equity but at least inclusion is being recognized as essential to our ability to generalize what we are learning.

I think the disease modifying drugs recently approved by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) are very hopeful. I am concerned about them because they have so few people of color in the trials. These drugs are most effective in early stages of the disease and many people from minoritized communities do not get a diagnosis until late stages. This is all the more reason for communities to increase awareness and understand the importance of getting that diagnosis early. Communities need our help and I am excited that the Alzheimer’s Association and other organizations are seeing the benefit of working with communities, particularly underserved and underrepresented ones.

Another big trend I am excited about is the Lancet Commission’s report, initially released a few years ago, that said about 40% of dementia could be alleviated if we could change or modify behaviors in early, middle and late life. People in rural area and poor communities will need to have support to address these social drivers in early, middle and late life. Increasing awareness, behaviors and circumstances will require policy change. I am excited about the opportunity to get cognitive assessments at annual visits. Families and communities must become aware and address this disease and its risks earlier.

There is great work in biomarkers and genomics that will address earlier and non-invasive diagnoses and even better therapies. It is a hopeful time in Alzheimer’s and the research is moving at such a rapid pace, in those in early and midlife too centenarians. It is truly an exciting time.

What is the most exciting part of AAIC for you?

AAIC is exciting because the best science, around the world, converges! Bringing the best minds together in one city, and bringing the community to the meeting is simply fantastic! You can walk around to the posters or sit in the plenaries and get many ideas. Folks are willing to share and collaborate. It is one of the more invigorating things I do in the scientific community.

I usually support one of the mentoring breakfasts (at AAIC), just talking to young people, that next generation of scientists that will be great in this space, talking to them about careers and what it takes to be a great scientist, and about balancing families with career. That is exciting.

This year you were honored with a lifetime achievement award, the Bengt Winblad Award. What does that award mean to you or signify to you? How does it reflect on your career?

Well, it is lifetime achievement, so it probably says I need to retire! *laughs*

It is nice for your peers and your colleagues to say “Job well done.” There is value to that. But we don’t do the work for this purpose. More importantly for me is that perhaps another investigator could be inspired to be courageous to do this work. If young investigators who witnessed me receiving the award could dare to make inclusion a part of their work to end Alzheimer’s, then the award is even more meaningful. So many people could have been the recipient of this award and I have benefitted from the work and collaboration of many of them. My hope is that the award will inspire others to stay true to the cause, irrespective of race, ethnicity or ancestry.

What would you like to see for AAIC in the future?

I want to see more community engagement work. I also want to see more work in the inclusion space. I want to see more people of color donating brain tissue, participating in all types of trials and clinical studies, not because the funder requires it, but because it is a moral and social just obligation to include all communities so that what we learn can be generalized to everyone. I would love to see more AAIC sessions for the lay community and for policy makers. Connecting them to the science is necessary.